Assessment of Agricultural Education Needs for Women in Agric business in Gombe Implications of Poverty Reduction

CHAPTER TWO

LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Conceptual Framework

2.1.1 Concept of Needs

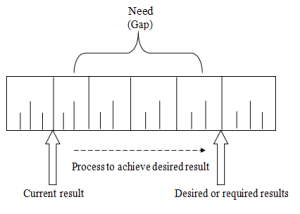

Needs are simply the differences between an individual’s current achievements and his/her desired accomplishments. Thus, needs most commonly represent discrepancies between the individuals ambitions and the results of his/her current performance (Watkins, West- Meiers & Visser 2012).

Figure 1 Relating Needs to discrepancies between What Is (Current Results) and What Should Be (Desired Results) adopted from Kaufman, Oakley-Brown, Watkins, and Leigh (2003) and Watkins (2007).

Improving performance, as used above is the move from achieving current results to accomplishing desired results. Thus, improving refers to the measured progress from a less- than-desirable state to a desirable state whereas performance refers to the results no matter the classification it is given by an organization i.e. products, outputs, outcomes, impacts, or some combination of these. Results are interrelated and interdependent; impacts depend on products, for instance, just as outputs should contribute to outcomes. Without the products of individual staff members, organizations would not have deliverables to provide to clients nor would communities benefit from the outcomes or effects of those deliverables. Therefore, alignment of results is critical to success, much more so than the titles we give those results. Embedded in the phrase improving performance is the notion that improving how people perform is also essential to accomplishing results, although performing and performance are not equivalent. Desired results are rarely accomplished without improvements in how people perform and therefore, performance is considered the combination of the process (that is, performing) and the desired results. Information need is construed in the sense of data or a set of data specially required enabling the user to make an appropriate decision on any related problem facing him or her at any particular time (Solomon 2002).

According to Dervin (1995), information represents an ordered reality about the nature of the world people live in. Research on information needs and information seeking concurs that information is tailored to the individual’s job and to their tasks within those jobs (Ingwerson 1996; Zeffane & Gul 1993).Information in an enterprise is important for the production process, the economy of products, technical quality, production capacity, and the market and market related needs, such as competitive intelligence. Mudukuti and Miller (2002) suggested that in the information age, dissemination of information and applying this information in the process of agricultural production will play a significant role in development of farm families. Similarly Sligo and Jameson (1992) have also stressed that farm women must be given training on latest technological skills and maximize production. Meanwhile, a pre-requisite to achieve this, is to assess the information needs of farm women. Information seeking behavior is a broad term encompassing the ways individuals articulate their information needs, seek, evaluate, and use the needed information. A cognition or information acquisition depends on the needs of individuals involved in special activities which may include various forms of agribusinesses. Information and communication sources could be classified into two broad types: internal and external. The information seeking process may require either or both of these sources. Information needs could be satisfied by either considering farm women individually as self-sustaining information systems or to look at them as a community interacting with each other and with systems within their immediate environment (Kempson 1986; Ikoja-Odongo & Ocholla 2003).A needs-assessment, according to the Borich concept, identifies the performance requirements and the “gap” between existing and needed information (Wingenbach, 2013). Altschuld and Witkin (1995) defined needs assessment as a series of procedures for identifying and describing both present and desired states in a specific context, deriving statements of need and placing the needs in order of priority for later action (Brasier, Barbercheck, Kiernan, Sachs, Schwartzberg &Trauger,2009).

In the modern age of consumerism, needs assessment consists of engaging the stakeholders in community development processes (Tipping, 1998; Yoder-Wise, 1981). Boyle (1981) maintained that evaluation involves comparison between the present situation and the established criteria. As such, the challenge in assessing the educational needs of a farmer is to compare the present situation with the ideal or desired situation. This process involves the making of judgment. The judgment should show the causes of the present situation and accordingly help programmers in making recommendations aimed at altering the situation to its desired state. The judgments about the suitability of different programs to farmers should be made in consultation with the farmers, as they are the ones to be affected by the change (Mead, 1955; Boyle, 1981; McMahon, 1970). The work of women makes up some 43 percent of agricultural inputs, yet they lag far behind in reaching their full potential or remuneration for their labours in comparison with men in agriculture. In general, rural women in agriculture do not have equal access to land rights, education, agriculture training, seeds, water or tools. They also lag behind their male counterparts in accessing information, training and the latest technologies (FAO, 2014b). The relevance of this is supported by Balit (2006) who points out that the least expensive input for rural development is knowledge. This awareness is echoed by Muvezwa (2006) who suggests that information is now a fifth factor of production in addition to land, capital, labor, and technology. Leeuwis and Van den Ban (2004) recognize that globally, useful information and knowledge on agriculture is in most cases, held by a collection of actors known as Agricultural Information and Knowledge Systems (AIKS). The agricultural information transfer system consists of four main interrelated components namely development, documentation, dissemination, and diffusion (Gundu, 2009).Wayland, Sloan, Edmund des Brunner, Wilbur, & Hallenbeck (as cited in Uko, 1985) emphasized the importance of information in needs assessment when they stated that: “To build a program of adult education on the needs of adults requires the information which indicates what those needs are”. Cross (1979) also emphasized the importance of adequate information in achieving a successful needs assessment, when she upheld that information should always precede the technical or subject matter if meaningful needs assessment was to be achieved. According to McMahon (1970), learning to identify needs accurately means closing the gap between relevance and reality. In determining the educational needs of the farmer, the program planner should endeavor to be well acquainted with the present level of competence of farmers in farming as a vocation, their attitudes about farming, their farm operating skills, the operating practices employed by the farmers, their economic status, the farming practices peculiar to the usual techniques employed by the farmers and their judgment about their current farming practices (McMahon, 1970 & Knox, 1969). Other information necessary for meaningful assessment of educational needs of farmers should focus on what the desired situation should be. Evidence about desirable farming practices should come from research findings on appropriate farming techniques, value judgment of professionals and alternatives based on economic status, geographical location and opportunities created by government programs and legislation.

2.1.2 Concept of Poverty Reduction

Poverty is said to lie at the root of unattainable development (Morgan, 1996 &Yekeen, 2009). The interpretation is that, poverty is antithetical to sustainable development. It is against equity and it impinges on environmental limits. Indeed, ‘Sustainability is not just about economy or a given social condition, but coping with stress and insuring against stress. Rural poverty restricts alternatives available to people, restricts capacity for choice making and the pressure on the few available resources increase when people lack alternatives (Yekeen, 2009). Abbas (2012) proposed a rural poverty alleviation index of nine variables. These variables are: (1) Nutrition = food intake; (2) Clothing = use of clothes; (3) Shelter = occupancy of dwelling; (4) Health = health care services received; (5) Education = literacy and years of schooling; (6) Leisure = protection from over work; (7) Security = security in its broadest sense; (8) Social environment = social contacts and recreations; and (9) Physical environment = beauty, cleanliness, amenities and quietness.

There are government agencies and ministries established to implement government policies and programmes intended to provide employment, income generation and to boost increased agricultural production. (Ehisuoria & Aigbokhaebho,2014).They are expected to; among others things provide infrastructure and social services to ameliorate poverty (Osawe, 2004).Various poverty alleviation programmes have been implemented in Nigeria, but the level of success is minimal. Low agricultural productivity, unemployment, poor or lack of infrastructural facilities in the country, inefficient civil services and poor attitude to execution of government projects are among the reasons why the above programmes have not been able to achieve their objectives. The study by Osawe (2004) also revealed that shortage of capital is one of the challenges facing the industries. To solve the problem of financial constraints for rural industries in Nigeria, the government has put in place various schemes, programmes and policies to finance small and medium scale enterprises particularly in the rural areas which include national poverty eradication programme (NAPEP), and bank of industries (BOI). Despite these policies and programmes, the problem of finance is yet to be overcome because most of the rural entrepreneurs have no collateral security that qualifies them to secure the loan. One way to increase the competitiveness of an industry or product on the global market is to produce more efficiently. Increases in efficiency are captured by measuring the agricultural value added per worker, which is also a proxy for agricultural productivity (Ng & Siebert, 2009).

Agriculture has a great role to play in poverty reduction policies. This significance has been shown by a recent analysis provided by the World Bank (2008), which indicates that agricultural growth as opposed to economic growth in general is typically found to be the primary source of poverty reduction. Investment in agriculture is 2.5 to 3 times more effective in increasing the incomes of the poor than is non-agricultural investment. In particular, it can be argued that agricultural policies that manage to respect, enhance and integrate small holder’s practices, local norms, organizations and relations with more modern production systems and technologies can additionally carry high social capital gains, thus further enhancing value chain cooperation and coordination with benefits for all participants. Agricultural development is conceived as embedded in the wider rural livelihood framework and can effectively become a means to allow people to exit the emergency of subsistence and other basic needs fulfillment.

Smallholder farmers which comprise mainly women are significant actors in agriculture globally, producing over 50 % of the current food supply (Scherr, Wallace, & Buck, 2010). Taking distance from poverty for them is a pathway towards improved capabilities, and incremental freedom to gain access to services and express higher aspirations, far beyond simply increasing agricultural yields and household incomes as an end in and of itself (Sen, 1999). Rapid increases in agricultural output, brought about by increasing land andlabour productivity, has made food cheaper, benefiting both the urban and rural poor, who spend much of their income on food. According to Smith and Haddad (2002), between 1980 and 2000 the real wholesale price of rice in Dhaka’s markets fell from 20 to 11 Taka per kg, bringing major benefits to poor consumers. Poor households typically spend 50–80% of their income on food including many poor farmers (Nugent, 2000). In addition, when the conditions are right, increasing agricultural productivity has increased the incomes of both small and large farmers and generated employment opportunities. These increases in income are particularly important because the proportion of people mainly dependent on agriculture for their income remains high ranging from 45% in East and South East Asia, to 55.2% in South Asia and 63.5% in sub- Saharan Africa (Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations statistics division [FAOSTAT] 2004).

A large body of evidence shows that higher agricultural productivity in Asia consistently raised farmers’ incomes despite declining market prices resulting from increased output. Small and medium sized farmers have not been excluded from these benefits (Lele & Agarwal, 1989; Lipton & Longhurst, 1989). Increased agricultural productivity has also created employment opportunities on farms, although this did not necessarily result in higher wages (Hazell & Ramasamy, 1991). Cross-country studies estimate that for every 1% increase in agricultural output, farm employment is increased by between 0.3 and 0.6% (Mellor, 2001). It is not just the landless that rely upon this source of income but several farmers who supplement their incomes by working on the farms of others. Poor households usually have limited human, social, physical and financial resources (Neven, Odera, Reardon & Wang 2009). Individuals and organizations with facilitation and/or brokering skills can help these households to pool their limited resources among themselves or with other actors (for example, NGOs or supermarkets) to achieve economies of scale, enter new markets, or access new resources, such as technical information or credit (World Bank 2006). Although the direct impact of farmer organizations on poverty seems relatively modest, organizations can have important indirect effects on poverty by fostering economic growth, creating employment, preventing buyers from benefiting at the expense of suppliers, building innovation capabilities, and protecting marginal groups (such as women or landless farmers) from further marginalization (World Bank,2012). They can also negotiate with authorities on behalf of their members and increase the public resources invested in poverty alleviation and affirmative action programs. Where poverty reduction is a central goal of economic policy, market access for producers assumes immense significance. Obi, Van Schalkwyk, & Tilburg(2012) also hold the view that how the food marketing system functions also has implications for the pace and level of regional development and so, the food marketing systems of developing countries have naturally been the subject of considerable academic and policy interest in recent times. Recent studies on the role of trade and market access have also shown that significant gains can accrue to farmers if systems and procedures for the marketing of surplus produce are improved, especially in the African context. Rodrik, Roe, Van Schalkwyk & Jooste (as cited in Obi, Van Schalkwyk,& Tilburg, 2012).

2.1.3 Profitable Agribusiness

According to Davis (as cited in Tersoo, 2013)Agribusiness is the sum total of all the operations involved in the manufacture and distribution of farm supplies, production operations on the farm and the strong processing-distribution of commodities and items. Agribusiness includes not only that productive piece of land but also the people and firms that provide the inputs (i.e. Seed, chemicals, credit etc.), process the output (i.e. Milk, grain, meat etc.), manufacture the food products (i.e. ice cream, bread, breakfast cereals etc.) and transport and sell the food products to consumers (i.e. restaurants, supermarkets etc.). (Babar, 2012). Agribusiness represents a four part system made up of;

(1)The agricultural input sector

(2)The production sector

(3)The processing-manufacturing sector and

(4)The transport and marketing sector.

To capture the full meaning of the term “agribusiness”, it is important to visualize these sectors as interrelated parts of a system in which the success of each part depends heavily on the proper functioning of the other two. Agribusiness is a complex system of input sector, production sector, processing- manufacturing sector, transport and marketing sector. Therefore, it is directly related to industry, commerce and trade, Industry is concerned with the production of commodities and materials while commerce and trade are concerned with their distribution (Babar, 2012).The objectives of Agribusiness include the development of a competitive and sustainable private sector led agribusiness sector, particularly in high value areas of horticulture, livestock and fisheries and thereby supporting rural development, employment generation and poverty alleviation, increasing productivity/reducing yield gaps, promoting commercially oriented agriculture activity and advancing high potential sectors (Khalid,2006).

Agribusiness has a large and rising share of GDP across developing countries, typically rising from under 20 percent of GDP to more than 30 percent before declining as economies transform. The majority of agro-enterprises are small, located in rural towns, and operated by households that often have wage labour and farming as additional sources of income (World Bank, 2007). Increasing agricultural productivity in Africa calls for broader policy and strategic frameworks that encompass agro-industrial and agribusiness services along with farming ( FAO as cited in Asenso-Okyere & Jemaneh, 2012).The agricultural system’s transformation will have the most impact when innovators have the explicit perspective that the green revolution and agro-industrial and agribusiness development must go hand-in-hand. This perspective will result in innovations that reduce poverty through broad-based economic growth, which includes enhanced food security, employment creation, added value and wealth across the economy’s farming and non-farming sectors (Asenso-Okyere & Jemaneh,2012).Scholars argue that empirical evidence shows an unequivocal inverse ratio between farm size and productivity when sustainable technologies and techniques are adopted (Cornia, 1985).

In the many agricultural contexts with labour intensive technology and practices, smallholder farmers tend to perform more productive farming mainly due to (a) higher motivation of labour input, which allows them to apply attention and skill to the farming method,

(b) the low substitutability of skilled labour for many sustainable cropping technologies and methods and (c) much of this skilled labour input has the capacity to enhance soil management and thus allow increase of productivity per unit of land. Small farmers also tend to apply a multiple crop farming strategy to take advantage of local peculiarities, in tune with the heterogeneous soil conditions and native agro-ecological systems (Perfecto & Vandermeer, 2010). In terms of comparative transaction cost advantages, small farms have been shown to have significantly lower labour- related transaction costs compared to large plantations, due mainly to the fact that the latter have to bear high costs of unskilled labour supervision and coordination whereas, large farms tend to have transaction cost advantages in terms of access to market information, capital technology and capacity to access land, input and output markets (Poulton, Dorward & Kydd 2010).

Do you need help? Talk to us right now: (+234) 08060082010, 08107932631 (Call/WhatsApp). Email: [email protected].IF YOU CAN'T FIND YOUR TOPIC, CLICK HERE TO HIRE A WRITER»